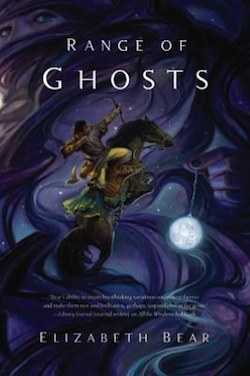

We know you’ve been waiting for a glimpse — here’s an excerpt from Elizabeth Bear’s Range of Ghosts, out on March 27:

Temur, grandson of the Great Khan, is walking away from a battlefield where he was left for dead. All around lie the fallen armies of his cousin and his brother, who made war to rule the Khaganate. Temur is now the legitimate heir by blood to his grandfather’s throne, but he is not the strongest. Going into exile is the only way to survive his ruthless cousin.

Once-Princess Samarkar is climbing the thousand steps of the Citadel of the Wizards of Tsarepheth. She was heir to the Rasan Empire until her father got a son on a new wife. Then she was sent to be the wife of a Prince in Song, but that marriage ended in battle and blood. Now she has renounced her worldly power to seek the magical power of the wizards. These two will come together to stand against the hidden cult that has so carefully brought all the empires of the Celadon Highway to strife and civil war through guile and deceit and sorcerous power.

1

Ragged vultures spiraled up a cherry sky. Their sooty wings so thick against the sunset could have been the column of ash from a volcano, the pall of smoke from a tremendous fire. Except the fire was a day’s hard ride east—away over the flats of the steppe, a broad smudge fading into blue twilight as the sun descended in the west.

Beyond the horizon, a city lay burning.

Having once turned his back on smoke and sunset alike, Temur kept walking. Or lurching. His bowlegged gait bore witness to more hours of his life spent astride than afoot, but no lean, long-necked pony bore him now. His good dun mare, with her coat that gleamed like gold-backed mirrors in the sun, had been cut from under him. The steppe was scattered in all directions with the corpses of others, duns and bays and blacks and grays. He had not found a living horse that he could catch or convince to carry him.

He walked because he could not bear to fall. Not here, not on this red earth. Not here among so many he had fought with and fought against—clansmen, tribesmen, hereditary enemies.

He had delighted in this. He had thought it glorious.

There was no glory in it when the men you killed were the husbands of your sisters, the sons of your uncles. There was nothing to be won when you fought against those with whom you should have shared a shield and a fireside. He could not find the fire of battle fever within himself. The ember had burned to a husk, and Temur was cold, and weary, and the lonely sorrow ran down his bones with an ache like cold.

Perhaps he was a ghost. For weren’t ghosts cold and hungry? Didn’t they crave the warmth and blood of the quick? The wound that gaped across Temur’s throat should have been his death. When it felled him, he’d had no doubt he was dying. Because of it—so obviously fatal, except that he had not died of it—nobody had thrust a second blade between his ribs or paunched him like a rabbit to make sure.

He had been left to lie among the others, all the others—his brother Qulan’s men and the men of his uncle Qori Buqa: the defenders of one man’s claim on Qarash and the partisans of the one who had come to dispute it—on the hard late-winter ground, bait for vultures who could not be bothered to hop from their feasts when he staggered close.

One vulture extended a char-colored head and hissed, wings broad as a pony blanket mantled over a crusting expanse of liver. The sootblack birds were foul and sacred. Tangled winter-crisp grass pulling at his ankles, Temur staggered wide.

But if Temur was a ghost, where were all the others? He should have been surrounded by an army of the dead, all waiting for the hallowed kindness of the carrion crows and of the vultures. Please. Just let me get away from all these dead men.

His long quilted coat was rust-stained with blood—much of it his own, from that temporary dying. It slid stickily against the thick, tight-woven silk of his undershirt, which in turn slid stickily against his skin. The fingers of his left hand cramped where they pinched flesh together along the edges of the long, perfect slice stretching from his ear to his collarbone.

The wound that had saved his life still oozed. As the sun lowered in the sky and the cold came on, blood froze across his knuckles. He stumbled between bodies still.

The fingers of his right hand were cramped also, clutching a bow. One of the bow’s laminated limbs was sword-notched to uselessness. The whole thing curled back on itself, its horsehair string cut. Temur used it as a walking stick, feeling it bend and spring under his weight with each step. He was beyond suffering shame for misusing a weapon.

The Old Khagan—the Khan of Khans, Temur’s uncle Mongke, son of the Great Khagan Temusan, whose enemies called him Terrible—was dead. This war was waged by Mongke’s would-be heirs, Qulan and Qori Buqa. Soon one of them would rise to take Mongke Khagan’s place—as Mongke Khagan had at the death of his own father—or the Khaganate would fall.

Temur, still stumbling through a battlefield sown heavy with dead mares and dead men after half a day walking, did not know if either his brother or his uncle had survived the day. Perhaps the Khaganate had fallen already.

Walk. Keep walking.

But it was not possible. His numb legs failed him. His knees buckled. He sagged to the ground as the sun sagged behind the horizon.

The charnel field had to end somewhere, though with darkness falling it seemed to stretch as vast as the steppe itself. Perhaps in the morning he would find the end of the dead. In the morning, he would have the strength to keep walking.

If he did not die in the night.

The smell of blood turned chill and thin in the cold. He hoped for a nearby corpse with unpillaged food and blankets and water. And perhaps a bow that would shoot. The sheer quantity of the dead was in his favor, for who could rob so many? These thoughts came to him hazily, disconnected. Without desire. They were merely the instincts of survival.

More than anything, he wanted to keep walking.

In the morning, he promised himself, he would turn south. South lay the mountains. He had ridden that far every summer of his young life that had not been spent campaigning. The wars in the borderlands of his grandfather’s empire had sometimes kept him from joining those driving the herds to his people’s summer ranges—where wet narrow valleys twisted among the stark gray slopes of the Steles of the Sky, where spring-shorn sheep grazed on rich pasturage across the green curves of foothills. But he had done it often enough.

He would go south, away from the grasslands, perhaps even through the mountains called the Range of Ghosts to the Celadon Highway city of Qeshqer. Away from the dead.

Qeshqer had been a Rasan city before Temur’s grandfather Temusan conquered it. Temur might find work there as a guard or mercenary. He might find sanctuary.

He was not dead. He might not die. When his throat scabbed he could capture some horses, some cattle. Something to live on.

There would be others alive, and they too would be walking south. Some of them might be Temur’s kinsmen, but that could not be helped. He’d deal with that when it happened. If he could find horses, Temur could make the journey of nine hundred yart in eight hands of days. On foot, he did not care to think how long he might be walking.

If Qulan was dead, if Qori Buqa could not consolidate his claim, the Khaganate was broken—and if he could, it held no refuge for Temur now. Qarash with its walled marketplaces, its caravanserais, its surrounding encampments of white-houses—the round, felt-walled dwellings Temur’s people moved from camp to camp throughout the year—had fallen. Temur was bereft of brothers, of stock, of allies.

To the south lay survival, or at least the hope of it.

Temur did not trust his wound to hold its scab if he lay flat, and given its location, there was a limit to how tightly he could bind it. But once the long twilight failed, he knew he must rest. And he must have warmth. Here on the border between winter and spring, the nights could still grow killing cold. Blowing snow snaked over trampled grass, drifting against the windward sides of dead men and dead horses.

Temur would take his rest sitting. He propped the coil of his broken bow in the lee of the corpse of a horse, not yet bloating because of the cold. Tottering, muddy-headed with exhaustion, he scavenged until he could bolster himself with salvaged bedrolls, sheepskins, and blankets rolled tightly in leather straps.

He should build a fire to hold off the cold and the scavengers, but the world wobbled around him. Maybe the wild cats, wolves, and foxes would be satisfied with the already-dead. There was prey that would not fight back. And if any of the great steppe cats, big as horses, came in the night—well, there was little he could do. He had not the strength to draw a bow, even if he had a good one.

No hunger moved him, but Temur slit the belly of a war-butchered mare and dug with blood-soaked hands in still-warm offal until he found the liver. Reddened anew to the shoulders, he carved soft meat in strips and slurped them one by one, hand pressed over his wound with each wary swallow. Blood to replace blood.

He would need it.

There was no preserving the meat to carry. He ate until his belly spasmed and threw the rest as far away as he could. He couldn’t do anything about the reek of blood, but as he’d already been covered in his own, it seemed insignificant.

Crammed to sickness, Temur folded a sweat-and-blood-stiff saddle blanket double and used it as a pad, then leaned back. The dead horse was a chill, stiff hulk against his spine, more a boulder than an animal. The crusted blanket was not much comfort, but at least it was still too cold for insects. He couldn’t sleep and brush flies from his wound. If maggots got in it, well, they would keep the poison of rot from his blood, but a quick death might be better.

He heard snarls in the last indigo glow of evening, when stars had begun to gleam, one by one, in the southern sky. Having been right about the scavengers made it no easier to listen to their quarrels, for he knew what they quarreled over. There was some meat the sacred vultures would not claim.

He knew it was unworthy. It was a dishonor to his family duty to his uncle. But somewhere in the darkness, he hoped a wolf gnawed the corpse of Qori Buqa.

Temur waited for moonrise. The darkness after sunset was the bleakest he had known, but what the eventual, silvery light revealed was worse. Not just the brutal shadows slipping from one corpse to the next, gorging on rich organ meats, but the sources of the light.

He tried not to count the moons as they rose but could not help himself. No bigger than Temur’s smallest fingernail, each floated up the night like a reflection on dark water. One, two. A dozen. Fifteen. Thirty. Thirty-one. A scatter of hammered sequins in the veil the Eternal Sky drew across himself to become Mother Night.

Among them, no matter how he strained his eyes, he did not find the moon he most wished to see—the Roan Moon of his elder brother Qulan, with its dappled pattern of steel and silver.

Temur should have died.

He had not been sworn to die with Qulan, like his brother’s oath-band had—as Qulan’s heir, that would have been a foolish vow to take—but he knew his own battle fury, and the only reason he lived was because his wounds had incapacitated him.

If he never saw blood again . . . he would be happy to claim he did not mind it.

Before the death of Mongke Khagan, there had been over a hundred moons. One for Mongke Khagan himself and one for each son and each grandson of his loins, and every living son and grandson and great-grandson of the Great Khagan Temusan as well—at least those born while the Great Khagan lived and reigned.

Every night since the war began, Temur had meant to keep himself from counting. And every night since, he had failed, and there had been fewer moons than the night before. Temur had not even the comfort of Qori Buqa’s death, for there gleamed his uncle’s Ghost Moon, pale and unblemished as the hide of a ghost-bay mare, shimmering brighter among the others.

And there was Temur’s as well, a steely shadow against the indigo sky. The Iron Moon matched his name, rust and pale streaks marking its flanks. Anyone who had prayed his death—as he had prayed Qori Buqa’s—would know those prayers come to naught. At least his mother, Ashra, would have the comfort of knowing he lived . . . if she did.

Which was unlikely, unless she had made it out of Qarash before Qori Buqa’s men made it in. If Qori Buqa lived, Temur’s enemies lived. Wherever Temur walked, if his clan and name were known, he might bring death—death on those who helped him, and death on himself.

This—this was how empires ended. With the flitting of wild dogs in the dark and a caravan of moons going dark one by one.

Temur laid his knife upon his thigh. He drew blankets and a fleece over himself and gingerly let his head rest against the dead horse’s flank. The stretching ache of his belly made a welcome distraction from the throb of his wound.

He closed his eyes. Between the snarls of scavengers, he dozed.

The skies broke about the gray stones of high Ala-Din. The ancient fortress breached them as a headland breaches sea, rising above a battered desert landscape on an angled promontory of winderoded sandstone.

Ala-Din meant “the Rock.” Its age was such that it did not need a complicated name. Its back was guarded by a gravel slope overhung by the face of the escarpment. On the front, the cliff face swept up three hundred feet to its summit, there crowned by crenellated battlements and a cluster of five towers like the fingers of a sharply bent hand.

Mukhtar ai-Idoj, al-Sepehr of the Rock, crouched atop the lowest and broadest of them, his back to the familiar east-setting sun of the Uthman Caliphate. Farther east, he knew, the strange pale sun of the Qersnyk tribes was long fallen, their queer hermaphroditic godling undergoing some mystic transformation to rise again as the face of the night. Farther east, heathen men were dying in useful legions, soaking the earth with their unshriven blood.

And that concerned him. But not as much as the immediate blood in which he bathed his own hands now.

Twin girls no older than his youngest daughter lay on the table before him, bound face to face, their throats slit with one blow. It was their blood that flowed down the gutter in the table to fall across his hands and over the sawn halves of a quartz geode he cupped together, reddening them even more than the sun reddened his sand-colored robes.

He stayed there, hands outstretched, trembling slightly with the effort of a strenuous pose, until the blood dripped to a halt. He straightened with the stiffness of a man who feels his years in his knees and spine, and with sure hands broke the geode apart. Strings of half-clotted blood stretched between its parts.

He was not alone on the roof. Behind him, a slender man waited, hands thrust inside the sleeves of his loose desert robe. Two blades, one greater and one lesser, were thrust through his indigo sash beside a pair of chased matchlock pistols. The powder horn hung beside his water skin. An indigo veil wound about his face matched the sash. Only his eyes and the leathery squint lines that framed them showed, but the color of his irises was too striking to be mistaken for many others—a dark ring around variegated hazel, chips of green and brown, a single dark spot at the bottom of the left one.

Al-Sepehr had only seen one other set of eyes like them. They were the eyes of this man’s sister.

“Shahruz,” he said, and held out one half of the stone.

Shahruz drew a naked hand from his sleeve and accepted the gory thing with no evidence of squeamishness. It was not yet dry. “How long will it last?”

“A little while,” he said. “Perhaps ten uses. Perhaps fifteen. It all depends on the strength of the vessels.” The girls, their bodies too warmed by the stone and the sun to be cooling yet. “When you use it, remember what was sacrificed.”

“I will,” said Shahruz. He made the stone vanish into his sleeve, then bowed three times to al-Sepehr. The obeisance was in honor of Sepehr and the Scholar-God, not the office of al-Sepehr, but alSepehr accepted it in their stead.

Shahruz nodded in the direction of the dead girls. “Was that necessary? Saadet—”

“I cannot be with your sister always.” Al-Sepehr let himself smile, feeling the desert wind dry his lips. “My wives would not like it. And I will not send you into the den of a Qersnyk pretender without a means of contacting me directly. All I ask is that you be sparing of it, because we will need it as well as a conduit for magic.”

Shahruz hesitated, the movement of his grimace visible beneath his veil. “Are we dogs, al-Sepehr,” he asked finally, reluctantly, “to hunt at the command of a pagan Qersnyk?”

Al-Sepehr cut the air impatiently. “We are jackals, to turn the wars of others to our own advantage. If Qori Buqa wants to wage war on his cousins, then why should we not benefit? When we are done, not a kingdom, caliphate, or principality from Song to Messaline will be at peace—until we put our peace upon them. Go now. Ride the wind as far as the borderlands, then send it home to me once you have procured horses and men.”

“Master,” Shahruz said, and turned crisply on the ball of his foot before striding away.

When his footsteps had descended the stair, al-Sepehr turned away. He set his half of the stone aside and bathed his hands in sunhot water, scrubbing under the nails with a brush and laving them with soap to the elbow. When he was done, no trace of blood could be seen and the sky was cooling.

He reached into his own sleeve and drew forth a silk pouch, white except where rust-brown speckled it. From its depths, he shook out another hollow stone. The patina of blood on this one was thin; sparkles of citrine yellow showed through where it had flaked away from crystal faces.

Al-Sepehr cupped his hands around it and regarded it steadily until the air above it shimmered and a long, eastern face with a fierce narrow moustache and drooping eyes regarded him.

“Khan,” al-Sepehr said.

“Al-Sepehr,” the Qersnyk replied.

The stone cooled against al-Sepehr’s palm. “I send you one of my finest killers. You will make use of him to secure your throne. Then all will call you Khagan, Qori Buqa.”

“Thank you.” The son of the Old Khagan smiled, his moustache quivering. “There is a moon I would yet see out of the sky. Re Temur escaped the fall of Qarash.”

“No trouble,” al-Sepehr said, as the beat of mighty wings filled the evening air. “We will see to it. For your glory, Khan.”

Range of Ghosts © Elizabeth Bear 2012